Algorithmic Content Discovery and Renewed Relevance for Human Tastemakers.

In his very personal piece about the closure of the independent video store he worked at for 25 years, Dennis Perkins makes interesting points about the limits of recommendation algorithms and the value of human, taste-based curation.

Admittedly, I don’t feel nostalgic about the twilight of brick-and-mortar video stores. I don’t want to sound flippant about people losing their jobs, but being “the man in the middle” is a very vulnerable position to be in. Distribution models change, and so do industries.

Still, Dennis Perkins’ perspective is interesting. Not only because he genuinely cares about film as art, not just content, but also because he considers his skill in recommending the right films to the right customers the most important part of his job:

A great video store is built on relationships, in some cases relationships that had gone on for years. Our customers were losing the people who’d helped shape their movie taste, who’d steered them toward things we knew they’d like and away from things they didn’t know they’d hate.

For people working in tech and product design, it’s easy to overlook the importance of the human component to content discovery. After all, we build tools and interfaces that enable users to find what they want on their own. But data science and recommendation algorithms don’t give you the answer as to why one user prefers one film over another. And what if the users don’t really know what they want either?

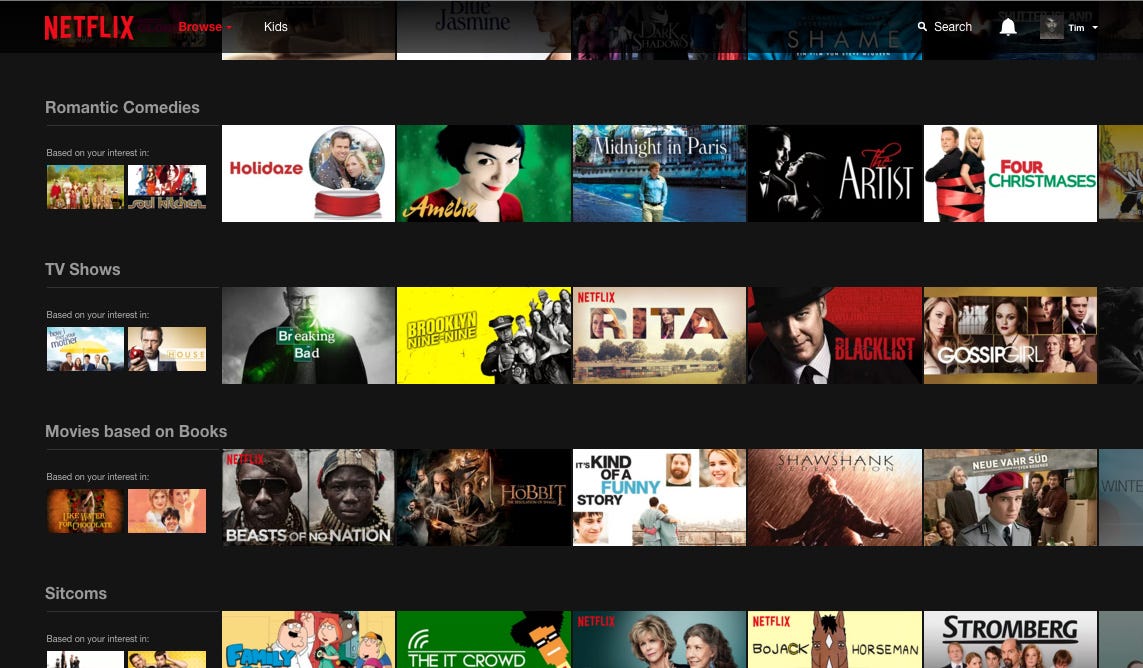

Dennis Perkins is right: Too often, digital content discovery sucks. Even on a brilliant service like Netflix. Finding the right movie to watch on a night in can turn into a 45-minute ordeal that ends in merely settling on something.

The problem is not that you have too much choice. As Dennis points out, you actually have less choice on services like Netflix or Hulu than in a well-stocked video store. The problem is that you don’t feel empowered to make a decision.

More often than not, recommendations seem meaningless or arbitrary to a point where it’s not clear if they are really based on your viewing behavior and your preferences. To narrow down their choices, users have to look for help elsewhere: By picking movies from user lists on IMDb or Rotten Tomatoes, reading movie reviews or asking their friends for cool things to watch. Making sense of the available choices is now the users’ responsibility.

This doesn’t mean that Netflix is a broken product. But it illustrates the limitations of algorithmically guided content discovery. Even the smartest recommendation engine is, at it’s core, an unintelligent helper that is only as good as the data it is fed with.

For many purposes, algorithms are good enough, even excellent. Spotify’s Discover Weekly features delightful, algorithmically personalized playlists. But streaming a four minute song isn’t much of a commitment, neither in time nor attention — two increasingly valuable resources. And even Spotify sometimes doesn’t get it right.

Maybe, in the future, an artificial intelligence with deep empathy and artistic sensibilities will get why I love one film but hate another, even if their metadata matches up to ninety-nine percent. Until we get there, human curation is becoming more and more relevant.

Apple’s Beats 1 radio, with its human DJs, artist-picked songs and thematic programming, has been called the one feature of Apple Music that sets it apart from the competition. Spotify introduced a similar concept called In Residence.

Google’s Eric Schmidt considers this an “elitist taste-making process”. Maybe that’s the point: Taste is not democratic. It’s subjective and uninterested in the opinion of the masses. Real curation is about intent and making choices.

Even as streaming turns video stores into artifacts of the past, the ability of tastemakers to help us make informed choices remains the most meaningful way for people to discover unknown pleasures.